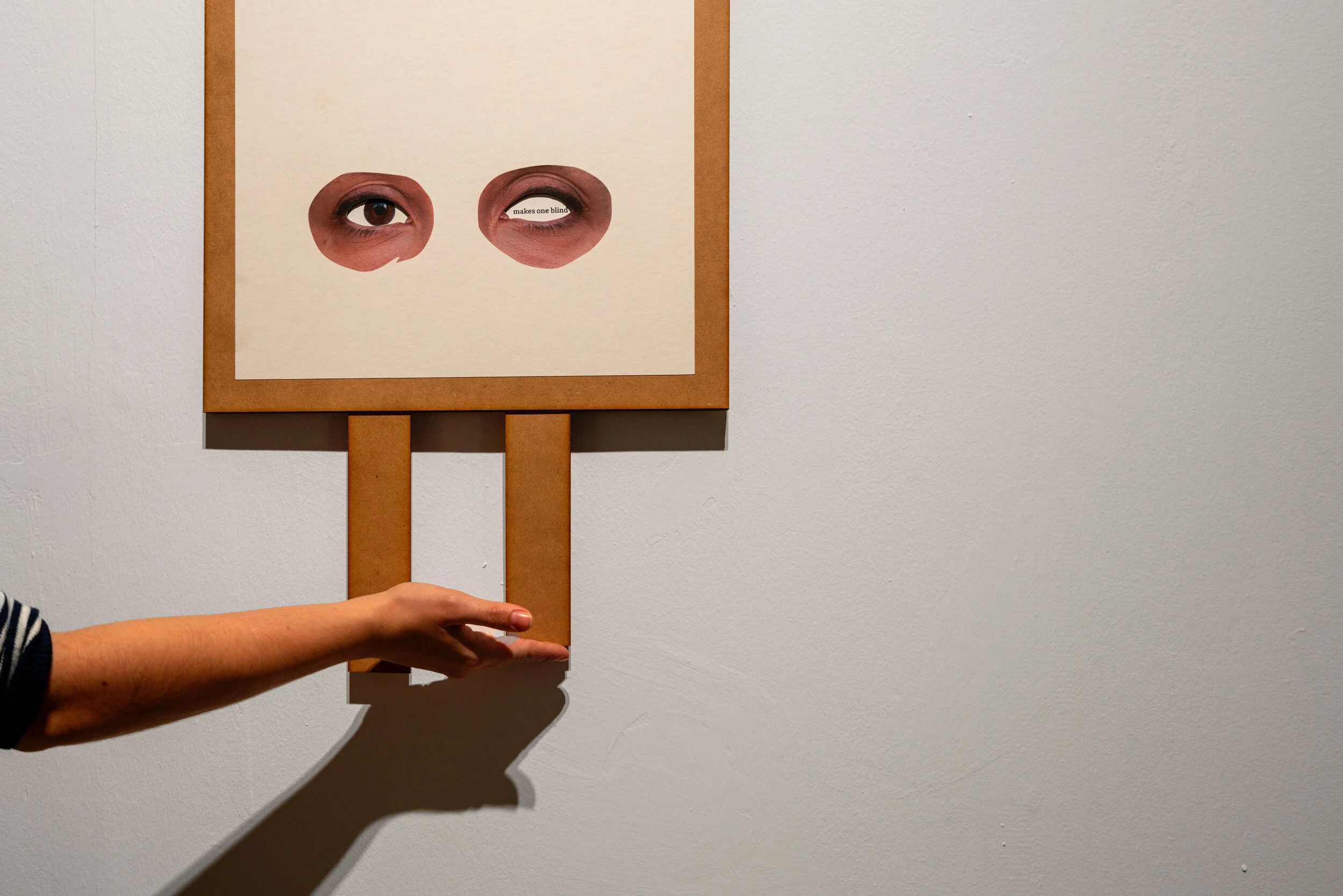

Too much insight (Feraset), 2020; print on mdf (mdf üzeri baskı). 98x40cm. Exhibition credits: Merve Ertufan, Waiting on a scratch, Depo, Istanbul, 2020-2021. Photography credit: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

"riddles, deaths and detours"

A conversation with Merve Ertufan

Tomris Melis Golar

7-8 min. read / scroll down for text in Turkish

Merve Ertufan occupies gaps in the mind and turns questionable sides of the self into new topics of inquiry by manifesting riddles, paradoxes and repetitions. She "mesmerizes" the viewers, so to speak, by pulling them into an invisible spiral with a physical twist and by urging them into a loop with dilemmas and repetitions within the exhibition space. She seeps into the depths of our minds through random questions, language twists, semi-real stories and brain teaser riddles. I have conducted a delightful interview with Merve Ertufan on her solo show Waiting on a Scratch that brings together several installations, videos and text-based works from her few latest years. The exhibition is on view at Depo between November 21, 2020 – January 15, 2021.

How would you briefly describe Waiting on a Scratch?

Waiting on a Scratch is an exhibition that is made out of 6 works that I worked on 2016-2020. It is an exhibition that unfortunately demands the physical presence and engagement of the viewer with its 3 video installations, a spatial installation, an interactive work and a book. (I say unfortunately, because the exhibition coincided with the second wave and the curfews.)

In the exhibition I try to slow down the experience of time, and offer a space for acts of rest, reflection and evaluation. I investigate the processes, formations and discrepancies that are often concealed behind language, expressions and repeated actions of our day-to-day experiences, moving through inquiries on selfhood, cognition and consciousness.

Exhibition credits: Merve Ertufan, Waiting on a scratch, Depo, Istanbul, 2020-2021. Photography credit: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Does the pandemic have an impact on the process of this exhibition?

Currently, we are in the midst of trying to translate the experience of the exhibition onto the digital space due to the pandemic. However, since the works were not conceived to be experienced through a personal computer screen, the works become unwatchable when repeated without alterations. For example, the work titled Can an answer be surprising? which is able to run for 22 minutes at a calm pace in its installed space, has to be sped up about 75-80% for the flat experience of the screen. The viewer’s psychological and bodily experience behind a computer is distinctly different than the one in the exhibition space.

With this exhibition, my intention was to remove life from its fast, focused, and unceasing flow; to create a space and distance that sets up a possibility for deceleration, deviation and reflection. I think the pandemic -without our intention to do so- is forcing us to slow down, and confront certain topics that we have been avoiding. It makes for a powerful confrontation with the fundamentals of being human, alive and existing on this earth; things we usually keep out of sight and out of mind. In this way, even if the exhibition content hadn’t changed much from April to November, it is clear that the context we are in -hence the context of the works as well- has changed quite drastically. I hope that the audience will encounter a companion of sorts with these works, one that contemplates on similar issues.

In the exhibition there are works where you treat the profoundness of language, mind and subconscious. Though it is possible to trace such elements in your previous works, still the distinctness in your methods and your language compels the attention. How do you see this change?

I think instead of the subconscious, the exhibition deals with the conscious and unconscious duality. Rather than psychoanalysis, the works delve into topics of language, mind and consciousness through the lens of cognition and neuroscience.

I guess I used to be more influenced by psychology in my previous works; those days I felt a need to support my works with documentary/evidential backing. For example, in works like Compliments or Sketch, I followed an artistic process of formulating rules for an environment, entering it and observing how the said environment formed our actions that were belatedly made visible through the video camera. In these works there was a prevailing effort to gain distance on myself and/or the medium, an attempt to gaze from outside. Somewhat experimental, a curiosity as to what kind of psychology would take over if we were to place this and that limitations on the subjects, a process that would later be edited and presented to the viewer.

However at the core of these works, there lies a belief -nevertheless doubtful- in the existence of what we call the ‘self’. In this regard, I think I was conducting a search for a true ‘self’ that would withstand all these trials in different environments.

Instead, today I employ knowledge retained from cognitive and neurological perspectives, and completely accept ‘self’ to be a speculation. This has helped me shed the need to provide documentary and/or evidential backing. A change for which I recognize Home Workspace Program of Ashkal Alwan in Beirut as being the major catalyst. I no longer search for a ‘self’; instead, I accept fictive narratives, and focus on medium oriented encounters mostly through text.

Can an answer be surprising?, 2017-20; video installation. 22 minutes. Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

The article of the exhibition written by L. İpek Ulusoy Akgül mentions your drawing parallels to Thomas Metzinger's 'Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self'. Can we hear these parallels from you too?

That is an extremely interesting and deeply challenging book actually. It is one of the two sources for the split I was just mentioning (the other is “Nihil Unbound” by Ray Brassier, especially the first three chapters).

Philosopher T. Metzinger, in his quest to investigate his personal out-of-body experiences/phenomena during sleep from his youth, goes on to answer questions of what it means to be human, how do we experience ourselves, and what are these things that we call will, self, perception, etc. At the core of the work lies the fact that we are not able to see how we think, which is to say we don’t know how we operate, we don’t know how an idea comes or goes, how we perceive an object, or how we perceive a subject. At this point, where we are not able to open up our skulls and see how the neurons fire, this philosophy book talks about what kind of myths/legends take over to fill that void. It is a substantial work that takes part in the current whole post-human, inhuman, nonhuman, human and artificial intelligence discourse; and, -unlike Metzinger's “Being No One”- this book is intended for a wider audience with a less technical language.

Although, I’m not sure if it can be called drawing a parallel. I think these two books informed the workings of all the projects in the exhibition.

Orbit, 2020; two channel video installation, linoleum print on walls. Loop. Exhibition credits: Merve Ertufan, Waiting on a scratch, Depo, Istanbul, 2020-2021. Photography credit: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Although you said that you are freed from the feeling of grounding the themes on proofs and records, I still think that you have a tendency of keeping strong references. Apart from Metzinger are there any other references that influenced you and this exhibition?

You’re so right. The works in the exhibition contain elements of what we may call anecdotal and autobiographical fictions, told in the form of first person singular. However, I don’t feel like it’s my place to present these as just my thoughts, because at the end of the day these topics have been treated for thousands of years in many different religions and languages. So, I don’t try to form a sense of ‘I’; instead, I consult the expertise of people that have researched these topics for years in order to understand what these auto-fictional elements entail within the scope of the exhibition.

The exhibition has many sources. Some specific works were influenced by more smaller and specific parts of different references; but as major influences that impacted several works at the same time, I can count these: Ego-Tunnel, T. Metzinger; Nihil Unbound, Ray Brassier; Insurmountable Simplicities, Thirty-nine Philosophical Conundrums, Roberto Casati & Achille Varzi; The Infinite Image, Zainab Bahrani; Crow With No Mouth, Ikkyú; Forthcoming, Jalal Toufic.

Apart from these there are many others that seep into separate works, but I believe that list would be very long and detailed. Maybe we can mention them if they come up during the chat on specific works.

Exhibition credits: Merve Ertufan, Waiting on a scratch, Depo, Istanbul, 2020-2021. Photography credit: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

The video installation called Orbit encapsulates the viewer into a spiral both visually and bodily while accompanying the hypnotizing effect that is spread throughout the exhibition as a whole. As the work becomes site-specific the above mentioned harmony delicately addresses the features of the physical exhibition space. At this point I wonder about your sequence of production.

The installation titled Orbit, imagines a video projection that circles a column, the viewer around the video and sphinx prints on the surrounding walls. In the exhibition space (Depo), the columns are the dominant architectural feature, and exhibitions are often developed with regard to these. After the exhibition was confirmed, I visited this unique space and realized I wanted to do a site inspired work; and decided to make a work that puts a column in the center, rather than having all these columns exist in between works. That’s why in this project, what I had imagined as a cone in the beginning ended up becoming a semi-pseudosphere (somewhat like a trumpet’s bell); the shape came before everything else.

I went many ways before making up my mind on what to put on this shape. For a while, I thought I’d put an animation of a cheetah running, another time I thought of making a video inspired by the zoetrope. The content got sorted once I realized I wanted to put the sphinx on the walls to encircle the whole project.

Sphinxes are mythological characters that guard the threshold, often placed at the main gates of cities to monitor and control who enters and leaves the city. In this work, the Alacahöyük Sphinxes are there due to their transient and ambiguous nature. They are partly made of woman, lion, eagle, and snake, but never can they become a whole woman, lion, eagle or a snake. They exist neither inside, nor outside, neither part of the architecture, nor free standing. They assisted me in thinking through hybridity and indefinability. In the exhibition, the spaces between two sphinxes repeat as white and black. It became a project through which I was able to think about the absolute and the ambivalent.

A similar approach exists in the circling video in the middle. A video of transformation, an entity that constantly evolves without ever taking an absolute, whole, nor solid form. I used a creative commons licensed online program called Artbreeder (GANart) that uses some kind of machine learning to generate new images by combining many different images together. In this video, no image is pure, all images include many other images in different percentages within it. The bird image may have a bit of watch, a bit flower, and a bit of beer within it.

In some instances in the video the image gets very close to a definable object (by the audience). However, if we were able to pause the video in the moment one thinks they saw a “dog”, we would see that the dog is not truly (morphologically) a dog, but we might become aware of the other images that compose it.

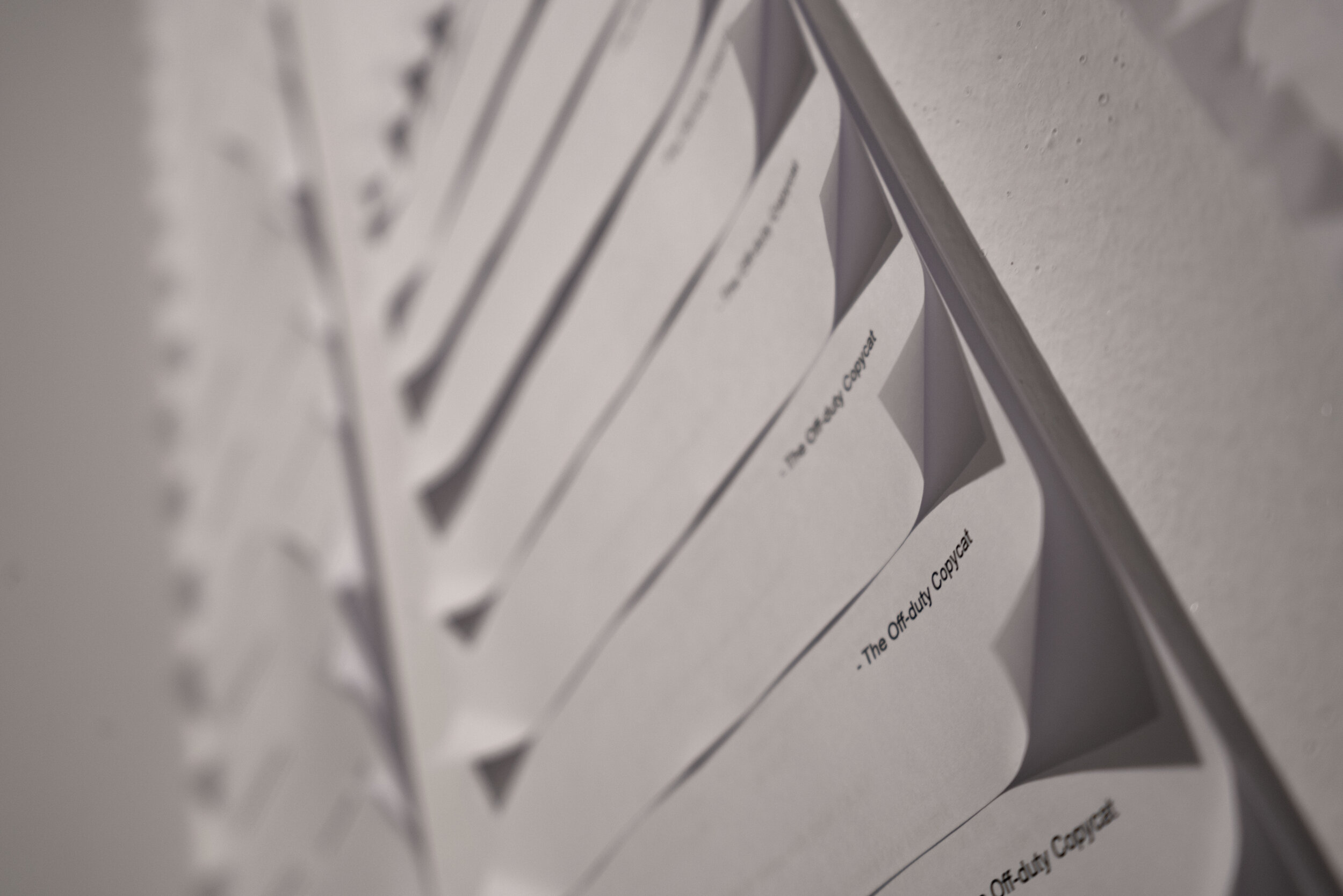

Copycat's strife with the original, 2018-20; printed A4 pages. Exhibition credits: Merve Ertufan, Waiting on a scratch, Depo, Istanbul, 2020-2021. Photography credit: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Why do these sphinxes stand there, can you reveal it a little bit more?

Sphinx has been accompanying me since the beginning actually. The exhibition’s starting point was language games and riddles; and one of the famous riddles takes place between the Sphinx and Oedipus. I got hooked from there, and sphinx is a very interesting character that seems to keep giving. Their double-ness opens up to infinity, their guarding of transitions and thresholds provide a strange concept of limit. Apart from these, things that Reza Negarestani and Z. Bahrani write about Lamassus seem adaptable to sphinxes to a certain extent. For example, Negarestani takes them as war machines, Bahrani writes about their transient existence and image power.

However, the riddle I just mentioned is the real reason that sphinx is the most prominent image within the exhibition. The riddle has many versions, one of them goes like this:

-Which creature walks on four feet in the morning, two feet at noon, and three feet in the evening?

In the story, the riddle was one which no one had answered correctly. But Oedipus answers right by saying “man”. And the Sphinx catches fire and dies.

While researching this riddle, I came across a text titled, “Oedipus' body & the riddle of the Sphinx”, published in 2006 at the Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism by Rob Baum, an academician who deals with performance, drama and body. In her text, Baum mentions how Oedipus lived with a disability all his life, due to his feet being bound as an infant and getting abandoned after the prophecy. In addition, she talks about how the story was a legend long before it was a tragedy, and that one version of the legend takes place pre-language. In all probability, Oedipus is able to solve the riddle because of his disabled feet, and in this version where he can’t speak words, he answers the riddle by pointing at himself.

I think this is why I turned the lines in the video in the counter direction of the rest, and placed the sphinxes at a height of the legs and knees of the visitors, possibly causing them to slightly lose balance/stability.

Lamassu is a Assyrian protective deity of thresholds. It has a human head, the body of a bull or a lion, and bird wings. Their main differences from the sphinx is that they often have male human heads and don’t have a known relationship with riddles.

Even though he borrows the term ‘war machine’ from Deleuze and Guattari, Negarestani’s war machine is not a nomadic force of dissidence opposite (or outside) of the State. It is a tactical tool born from and devoured by the (Un)Life of War for strategic advancement. Negarestani, accepts War as a radical outside, and not as war-as-machine. He talks about how Assyrians develop Lamassus as new and improved war machines to beat War (Cyclonopedia, 2008).

Copycat's strife with the original, 2018-20; printed A4 pages. Exhibition credits: Merve Ertufan, Waiting on a scratch, Depo, Istanbul, 2020-2021. Photography credit: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

I must admit you played with my equilibrium!

In the work called Copycat's Strife with the Original you are bringing up the subject of authenticity and disparity between the copycat and the original. Furthermore the notion of time plays an important role between these two. At this point, where does inspiration stand for you? Is it possible to talk about an absolute originality?

An absolute original is difficult, it may be easier to think of an absolute copycat. At least, we may be able to get close to an answer to the question “is it possible?”. Although, an absolute copycat won’t confirm the existence of an absolute original. God seems to be the absolute original in monotheistic traditions, I’m not sure about the polytheistic ones. Outside of the religious discourse, it seems we have yet to figure out the sources of our thoughts, actions and even material compositions. I guess when we talk about absolutes, the quest becomes too big. So big that we can’t distance ourselves enough to see the topic at hand in its totality.

In specificity of the work; Copycat’s strife with the original is a text-work printed on a4 papers, in which an “Off-duty Copycat” compares him/herself with the original. In the exhibition we have 720 copies placed on top of each other resembling a snake or a labyrinth. Each page has some section covered by the one above, and only in the one at the uttermost top can the viewer read the full text, which is also the one that came out of the printer first. In the text, the Copycat character seems to be obsessed with chronology; too aware of the fact that even if s/he were to watch with pure focus and repeat the Original’s actions as fast as possible, s/he can never actually be simultaneous with, nor precede the Original. The Original is free from the Copycat, proceeding with independent thoughts; whereas the Copycat is bound by the Original. I think this is why s/he tries to build self-worth through this text, which is written when s/he is actually off-duty. Since it’s not easy being a Copycat, can a complete imitation have a value on its own?

An echo too late, video still, courtesy of the artist. Exhibition credit: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021.

I believe there are so many details to touch upon within the work An echo too late. You are collating the tale of Khazar Princess and Narcissus with your own stories. While you tell the stories from others one can not hear any echo, however once you begin to tell your own story one can hear the belated echo of your voice. How did you set up this play of the self?

An echo too late is actually the work I worked on the longest in the exhibition. It started out as a sound work in 2016, which later extended to a much longer length and then shrank back to a 14 minutes video.

The project starts from a moment in which the narrator fails to recognize herself. In this phenomenon/illness, termed as facial agnosia, one loses the ability to recognize faces. Although in the story of the video, this only lasts for a few seconds, it prompts the narrator to describe her facial features, draw up a personal history, and share with the viewer her thoughts on the mechanisms of our processes of formulating a self.

Narcissus and Princess Ateh accompany the story, which is told in the singular first person tense, even though the voices are edited with echos from different sources. The appearance of these two characters are in fact related to the phenomenon of time in cognitive process. The conception of an acting “self” and an observing “selfhood” forms the basis of this project. Needless to say, the observer follows behind, and tries to make sense of the actions of the “self” in a speculative manner. However there is a lag in between. The video argues that this lag exists within a very delicate balance and can easily be disrupted.

Here, Narcissus and Ateh are presented as cases in which this temporal difference between the action and the perception, (or in the case of this work) the real and the image becomes extreme. Narcissus is a widely used reference, however I approached this story through the idea that the lake in question is enchanted. Because of the spell, Narcissus’ image exists in sync with real time, thus Narcissus is confined in an atemporal parenthesis between his gaze and the image’s gaze. So, he can’t remove his gaze, he turns into an absolute “self”, thereby transforming into a passive character with no agency. He slowly vanishes in front of his image.

Ateh is at the other end of the spectrum (Dictionary of the Khazars, Milorad Pavić). She is given two mirrors, on one of them the image appears after real time, on the other it appears prior to real time. Her eyelids were inscribed with letters to protect her from the enemies during her sleep; letters that are deadly for those who read it. The spell makes itself visible to her through these two mirrors, and ends up killing the princess. Because; while one of the mirrors shows the previous blink, the other one shows the latter. Ateh reads the letters between two blinks, and dies.

As you mentioned, in the video, stories of Narcissus and Ateh are narrated through a single sound from a central source, whereas the stories created and told by the narrator are heard through echoes, reflections and parallels. I made this particular choice, because I think that we can think more clearly and accurately while evaluating an abstract alternative or a phenomenon that is considered to be external. But actually, this is a project in which I try to go beyond reductive and detrimental binaries such as inside and outside, self and other, and reach towards a more global scale in relation to these questions.

Tumbling down with careful steps (Dikkatli adımlarla yuvarlanmak), 2020; artist book (sanatçı kitabı). Exhibition credits: Merve Ertufan, Waiting on a scratch, Depo, Istanbul, 2020-2021. Photography credit: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

To me one of the most significant reasons for being impressed by this exhibition was; that it does not hold any concern of delivering a direct opinion about socio-political current world problems. The notion of art works having to relate to or touch upon social or political situations has, in my eyes, become annoyingly persistent. In my opinion it is quite striking to discover such a self-oriented story as in Waiting on a Scratch that at the same time puts forth many existential topics tangling once in a while in our minds.

I think the most important aspect of contemporary art -even the term is coined after the “contemporary”- is that it deals with the issues of the present day. But I feel like we sometimes define the issues of the day in a limited manner. When we define today -the time period we’re addressing- in a narrow way, we find ourselves confined in a restricted present. Almost like Narcissus’ gaze. Confined within its own parenthesis, stuck, like a flickering light beam. My intention was in fact to expand this parenthesis, to disrupt the gaze and enable other perspectives to manifest themselves.

I don’t think it is necessary to address urgent issues of the day in order to engage with the sociopolitical realm. An artwork can be political through revealing the unknown, presenting utopias or reaching the masses; as well as through its aesthetic means; such as approach and methodology.

In Waiting on a Scratch, I worked on our perceptions of concepts such as the self, the body, ownership and agency that are constantly transforming along with technology- and perhaps they will go through many cycles of transformation in the future. I guess through this exhibition, I was able to present the means I use while trying to disentangle these existential questions -those that help me- for the viewer. I think the methodology I took on enables encounters, makes space for empathy and intends to slow things down overall.

Merve Ertufan - Waiting on a Scratch - Depo İstanbul (depoistanbul.net)

Thanks to: Merve Ertufan, Tomris Melis Golar, Gülşah Mursaloğlu & Mochu, Depo İstanbul.

Can an answer be surprising?, 2017-20; video installation. 22 minutes. Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

"bilmeceler, sonlar ve yoldan sapmalar"

Merve Ertufan ile sohbet

Tomris Melis Golar

7-8 dakika okuma süresinde

Merve Ertufan zihinsel boşlukları, benlikle ilgili şüpheli alanları bilmece, paradoks ve tekrarlarla yeni sorular haline getiriyor. İzleyiciyi, serginin içinde bulunan hem fiziki bir dairesellikle döngüselliğe hem de ikilem ve tekrarlarla görünmez bir sarmala sokarak adeta “büyülüyor”. Rastlantısal sorular, dilin içindeki oyunlar, yarı gerçek hikâyeler ve cevaplaması güç bilmecelerle aklın derinliklerine sızıyor. Merve Ertufan’la, son birkaç yılda ürettiği yerleştirmeleri, videoları ve metinsel işlerini bir araya getiren Kafakurcalayan sergisi hakkında keyifli bir röportaj gerçekleştirdik. Sergi, 21 Kasım 2020 – 15 Ocak 2021 tarihleri arasında Depo’da izlenebilir.

Kafakurcalayan sergisini kısaca nasıl anlatırsınız?

Kafakurcalayan, 2016-2020 yılları arasında üzerinde çalıştığım altı projenin bir araya gelip oluşturduğu bir sergi. Üç adet video yerleştirmesi, bir mekânsal yerleştirme, bir interaktif iş ve satın alıp götürebileceğiniz bir sanatçı kitabı bulunan, ne yazık ki izleyicinin fiziksel olarak sergi mekânında bulunmasını talep eden bir sergi (Ne yazık ki diyorum, çünkü tam ikinci dalgaya yakalandık).

Deneyimlenen zamanı yavaşlatmaya çalıştığım, koşturmaktan ziyade soluklanıp etrafa ve kendine bakma / değerlendirme eylemlerine alan açmaya çalıştığım bir sergi oldu bu. Günlük deneyimlerin, dilin, ifadelerin ve tekrarlanan eylemlerin ardında saklı kalmış süreçleri, oluşumları ve tutarsızlıkları araştırdığım; benlik, biliş ve bilinçle ilgili sorgulamalarla ilerlediğim bir sergi.

Sahtecinin sahici ile imtihanı, 2018-20; A4 baskı. Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Pandeminin bu serginin sürecine bir etkisi oldu mu?

Pandemi sebebiyle sergi deneyimini dijital ortamda yineleme denemesindeyiz. Ancak bilgisayar karşısında oturarak, kısıtlı bir odak noktası ile deneyimlenmesini düşünerek işleri yapmadığım için, projeler biraz değiştirilmeden ekrana aktarıldığı zaman izlenemez oluyorlar. Mesela mekânda Bir cevap şaşırtabilir mi? 22 dakika boyunca kendi sakin hızında ilerleyebilirken, bilgisayarda yüzde 75-80 hızlandırmak gerekiyor. İzleyicinin bilgisayar başındaki ve sergi mekânındaki psikolojisi ve bedensel deneyimi çok farklı.

Süratli akışından çıkarıp hayatı; biraz dönüp bakmaya, biraz değerlendirmeye alan tanıyan bir sergi oluşturma gibi bir niyetim vardı. Pandemi sanırım bu bahsettiğim yavaşlamaya -niyetimiz dışında- bizi zorlayarak soktu, bazı kaçtığımız konularla yüzleştirdi. Gözden ırak, aklımızdan uzak tuttuğumuz ama aslında insan olmanın, canlı olmanın ve dünya üzerinde var olmanın koşullarıyla zorla ve şiddetle karşılaştırdı bizi. Bu açıdan sergi Nisan’dan Kasım’a belki içerik olarak çok değişmese de, bizim içinde bulunduğumuz bağlamın değişmesi ile beraber işlerin de bağlamının değiştiği aşikar. Umuyorum ki, ziyaret eden izleyici benzer soruların üzerine düşünen bu işlerde bir gönüldaş, bir yoldaş bulur.

Serginin içinde dil, zihin ve bilinçaltının derinliklerini işlediğiniz çalışmalarınız mevcut. Bu serginin öncesinde ürettiğiniz yapıtlarda da bu ögeleri takip etmek mümkün fakat yöntemlerinizde ve dilinizde bir farklılaşma da dikkat çekiyor. Bu değişimi siz nasıl görüyorsunuz?

Sergide bilinçaltı yerine sanırım bilinç ve bilinçdışı ikiliği daha baskın. Psikanalizden çok, kognisyon (biliş) ve nöroloji üzerinden dil, zihin ve bilince yaklaşan projeler olduğunu düşünüyorum.

Sanırım daha önceki işlerimde psikolojiden daha çok besleniyordum, o projelerde hep bir belgeye/kanıta dayanma ihtiyacım oluyordu. Mesela İltifatlar ya da Eskiz gibi işlerde bir ortam yaratıp, kameranın karşısına geçip o ortamda nasıl hareket ettiğimize bakmaya yönelik bir sanatsal üretim sürecim vardı. Bu işlerde kendime/ortama mesafe koyma, dışarıdan bakma çabası bence çok baskındı. Bu ve şu kısıtları koyarsak bakalım nasıl bir psikoloji ortaya çıkacak gibi, hafif deneysel ama daha sonra kurgulanıp izleyiciye sunulan bir süreçti bu.

Ancak, sanırım bu işlerin en merkezinde “benlik” dediğimiz şeye şüpheli de olsa bir inanç vardı. Bu sebepten sanıyorum ki birçok farklı ortamda denemeler yapıp ortak, öz ve esas bir benlik bulma çabam / bir arayışım vardı.

Oysa bugün, özellikle bilişsel bilim (cognitive science) ve nörolojiden gelen bilgiler eşliğinde, benliği tamamen bir spekülasyon olarak kabul edip, belge oluşturma / kanıt oluşturma zorunluluğundan kurtulduğumu hissediyorum. Özellikle Beyrut’taki Ashkal Alwan’ın Home Workspace Programı’nın etkisini büyük ölçüde hissettiğim bir değişimde artık kurguyu iyice kabul ettiğim, öz bir benlik arayışından çıkıp, ortamsal karşılaşmalar üzerine çoğunlukla metin üzerinden oluşturduğum bir noktaya geldim.

Sergi metnini kaleme alan L. İpek Ulusoy Akgül, Thomas Metzinger’in “Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self” (Ego Tüneli: Zihin Bilimi ve Benlik Efsanesi) referansı ile paralellikler kurduğunuzdan bahsediyor. Bu paralellikleri sizden dinleyebilir miyiz?

O çok ilginç ve insanı zorlayan bir kitap aslında. Demin bahsettiğim kırılmanın da asıl kaynaklarından biri (diğeri ise Ray Brassier’in “Nihil Unbound” isimli kitabı; özellikle ilk üç bölümü).

Filozof T. Metzinger, özellikle gençliğinde birçok defa deneyimlediği uyku sırasında vücuttan çıkıp gezme hissiyatını/fenomenini araştırmak üzere çıktığı yolda, aslında insan olmak nedir, kendimizi nasıl deneyimliyoruz, irade, benlik ve algı nedir gibi soruları nörolojik çalışmalar çerçevesinde cevaplamaya çalışıyor. Kitabın en merkezinde nasıl düşündüğümüzü göremediğimiz; yani aslında insan olarak nasıl işlediğimizi bilmediğimiz; bir düşünce nasıl geliyor, nasıl gidiyor, bir objeyi nasıl algılıyoruz; bunları bilmediğimiz gerçeği bulunuyor. Kendi kafamızı açıp nöronların nasıl hareket ettiğini göremediğimiz bu noktada, bu boşluğu ne tür mitlerle/efsanelerle doldurduğumuza dair bir felsefe kitabı. İnsan sonrası (post-human), insan dışı (inhuman), insan olmayan (non-human), insan (human) ve yapay zeka (artificial intelligence) tartışmaları çerçevesinde önemli bir ayak oluşturmuş, “Being No One” isimli daha önceki teknik kitabına nazaran “Ego-tunnel” daha genel okuyucunun takip edebileceği bir dilde yazılmış bir kitap.

Buna paralellik denir mi bilmiyorum ama. Bence sergide bulunan bütün işlerin temel işleyişini oluşturdu bu iki kitap. Olanları o gözle anlamaya, işleri bu kafayla kurgulamaya çalıştığım bir sergi oldu sanki.

Too much insight (Feraset), 2020; print on mdf (mdf üzeri baskı). 98x40cm. Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Her ne kadar konuları kanıt ve belgelere dayandırma hissinden kurtulduğunuzu söylemiş olsanız da, ben yine de güçlü referanslara bir şekilde meylettiğinizi düşünüyorum. Metzinger’in dışında sizi ve bu sergiyi etkileyen başka referanslar da var mıydı?

Çok haklısın. Sergideki işler birinci tekil şahıstan, anekdotlardan oluşan otobiyografik özkurgu diyebileceğimiz unsurları içeriyor. Ama bu benim düşüncem diyerek ortaya atabileceğim bir yer değil gibi hissediyorum, bunlar birçok farklı dinde ve dilde binlerce yıl boyunca işlenmiş konular. Bu sergide bir “ben” kurgusu oluşturmaya çalışmıyorum, daha çok bu özkurgusal unsurları anlamak ve anlamlandırmak için bu konular üzerine uzun süre araştırma yapmış uzmanlardan yardım alıyorum, bilgi birikimlerinden yararlanıyorum.

Serginin birçok farklı yerden küçük küçük çekip çıkardığı bir sürü kaynağı oldu ama; birçok işi birden etkileyen kapsamlı referanslar olarak şunları sayabilirim: “Ego-Tunnel”, T. Metzinger; “Nihil Unbound”, Ray Brassier; “Insurmountable Simplicities: Thirty-nine Philosophical Conundrums”, Roberto Casati & Achille Varzi; “The Infinite Image”, Zainab Bahrani; “Crow With No Mouth”, Ikkyú; “Forthcoming”, Jalal Toufic.

Bunlar dışında tek tek işlere sızan farklı farklı kaynaklar var, ama o liste sanırım biraz uzun ve detaylı olur. İşler üzerine konuşurken konusu açılırsa bahsedebiliriz belki.

Yörünge, 2020; iki kanallı video yerleştirme, duvara linol baskı. Loop. Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Yörünge isimli video yerleştirmeniz izleyiciyi hem görsel hem de bedensel bir daireselliğin içine hapsederek, serginin geneline yayılan ve insanı hipnotize eden etkiye eşlik ediyor. Bu uyum videonun mekâna özgü bir eser halini almasıyla birlikte sergi mekânının fiziki özelliklerine de hoş bir referans veriyor. Aslında bu noktada eseri üretme sıranızı merak ediyorum.

Yörünge isimli iş bir sütunun etrafında 360 derece dönen bir video, onun etrafında dönen bir izleyici ve hepsini çevreleyen duvarlardaki sfenks baskılarından oluşuyor. Sergi mekânında ( Depo’da) sütunlar mimari olarak çok baskın ve sergiler hep bu sütunlar etrafında kuruluyor. Sergi kesinleştikten sonra mekâna ilk girdiğimde, bu özel ortamdan esinlenen, bu ortam için hazırlanmış bir proje yapmak istedim. Sütunların sadece işler arasında yer almasındansa bir işte sütunu tam ortaya koymak istedim. Bu sebeple bu projede, sütun etrafında dönen önceleri koni olarak hayal ettiğim ama daha sonra geometride semi-pseudosphere [yarım aykırı küre] olarak adlandırılan zurna ağzına benzeyen şekle evrilmiş yüzey her şeyden önce ortaya çıktı.

Bu şeklin üzerinde ne olmalı diye düşünürken bir çok farklı noktaya gittim, mesela bir ara bir çitanın koştuğu bir animasyonu yapmayı, bir ara da zeotroptan esinlenen bir video yapmayı düşündüm. Sfenkslerin duvarlarda ve bütün proje etrafında dönmesine karar verdiğim noktada ise içerik çözüldü.

Sfenksler eşikleri koruyan, özellikle şehir giriş-çıkışlarında / kapılarında yer alan mitolojik karakterler. Buradaki Alacahöyük Sfenksleri, daha çok ara-yaratık olma özellikleriyle yer alıyorlar. Ne tam kadın, aslan, kartal ya da yılan olabilen, ne tam içeride ne tam dışarıda, ne tek başına durabilen, ne tam mimarinin parçası olabilen, melez ve muğlak halleri üzerine düşündüm. Sergide iki sfenks arası bir beyaz, bir siyah oluyor. Mutlaklıklar ve muğlaklıklar üzerine düşündüğüm bir proje oldu.

Ortada dönen projeksiyonda da benzer bir işleyiş var aslında. Kendi içinde durmadan dönüşen hiçbir zaman tam/mutlak/somut bir şekil almayan, yani aslında dönüşümün kendisi var orada. Artbreeder (GANart) isimli internet üzerinden makine öğrenmesi (machine learning) kullanan herkesin kullanımına açık bir programı kullandım orada. Bu aracın bir özelliği birçok farklı imgeyi kombinleyerek yeni imge çıkarabiliyor olması. Özellikle bu projede, hiçbir imge salt haliyle var değil, her imge içinde birçok farklı imgeyi bulunduruyor. Kuşun içinde biraz saat, biraz çiçek, biraz bira bulunabiliyor.

Videoda, birçok kez izleyicinin neredeyse tanıyabileceği/tanımlayabileceği imgeler bulunsa da, ‘köpek’ gördüğünüzü düşündüğünüz yerde videoyu durdursak morfolojik olarak aslında tam köpek olmadığını, içinde başka imgelerin de bulunduğunu görmüş oluruz.

Orbit, detail, 2020; two channel video installation, linoleum print on walls. Loop. Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

O sfenksler neden oradalar, biraz daha açmanız mümkün mü?

Sfenksler aslında serginin başında beri bana eşlik eden karakterler. Serginin başlangıç noktasında dil oyunları ve bilmeceler bulunuyordu ve dünyanın en ünlü bilmecelerinden biri Sfenks ve Oidipus arasında geçiyor. Oradan bir takıldım ve sfenksler açtıkça açılan çok ilginç karakterler. İkilikleri sonsuzluğu açıyor, geçişleri ve eşikleri korumaları çok ilginç bir sınır anlayışı oluşturuyor. Bunlar dışında, Reza Negarestani ve Z. Bahrani’nin Lamassu üzerine yazdıkları da sfenksler için uyarlanabiliniyor. Mesela, R. Negarestani onları geliştirilmiş savaş makinası olarak alıyor, Z. Bahrani de muğlak varlıkları ve imgesel güçleri hakkında yazıyor.

Ancak bu sergi bağlamında imge olarak en baskın karakter olmasının sebebi demin bahsettiğim bilmece. Bilmecenin birçok versiyonu var, bir tanesi şöyle:

-Hangi yaratık sabah dört ayak üstünde, öğlen iki ayak üstünde ve akşam üç ayak üstünde yürür?

Kimsenin çözemediği bu bilmecenin cevabını Oidipus buluyor, ve hikâyeye göre “man” ya da “insan” der. Bilmecesi çözülen Sfenks alev alıp intihar eder.

Bu bilmece üzerine araştırma yaparken, performans, drama ve beden üzerine çalışan akademisyen Rob Baum’un 2006’da Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism’de çıkan “Oedipus' Body & The Riddle of the Sphinx” isimli bir yazısına denk geldim. Burada Oidipus’un kehanet sonrası bebekken nasıl ayaklarının bağlanıp terkedildiğinden, bu sebepten ömrünü bacaklarındaki engel ile yaşadığından bahsediyor. Bir de hikâyenin Tragedya’ya dönüştürülmeden önce bir efsane olduğundan, ve bu efsanelerden birinin dil-öncesi dönemde gerçekleştiğini anlatıyor Baum. Büyük ihtimalle kendi bedenindeki engeli sayesinde bilmeceyi çözebiliyor Oidipus ve dil ile ifade edemediği bu versiyonda cevabı kendine işaret ederek veriyor.

Bu sebepten sanırım sütun etrafındaki videoda ters tarafa dönen çizgiler ile biraz izleyicinin dengesiyle oynamak istedim. Sfenksleri de duvarda bacaklara/dizlere dolanabilecek yüksekliğe yerleştirdim.

Lamassu, insan kafalı, boğa ya da aslan vücutlu, kuş kanatlarına sahip Asurluların eşik koruyucu tanrısıdır. Sfenkslerden en büyük farkları insan kafasının genelde erkek olması ve bilmeceler ile bilinen bir ilişkisinin olmamasıdır.

Savaş makinası kavramını Deleuze ve Guattari’den ödünç almış olsa da, Negarestani’nin savaş makinası devlete karşı (ya da dışında) göçebe bir direniş değil, Savaşın Yaşam(sız)lığı ((Un)Life of War) tarafından stratejik avantaj sağlamak adına yutulmak için doğurulan, sadece bir taktik geliştirme yöntemidir. Negarestani, makina-olarak-savaş yerine Savaş’ı bir radikal dış (radical outside) olarak kabul eder, Asur’luların Savaş’ı yenmek için Lamassuları geliştirilmiş savaş makinası olarak görevlendirdiğinden bahseder (“Cyclonopedia”, 2008).

Sahtecinin sahici ile imtihanı, 2018-20; A4 baskı. Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Kendi adıma söyleyebilirim ki benim dengemle oynadınız!

Sahtecinin Sahici ile İmtihanı çalışmanızda kopya edenle orjinal arasındaki özgünlük ve farklılıklardan bahsediyorsunuz. Ayrıca zaman kavramı bu ikili arasında önemli bir rol oynuyor. Bu noktada esinlenme sizce nerede duruyor? Mutlak bir sahicilikten bahsetmek mümkün müdür?

Mutlak sahicilik çok zor, ama mutlak sahtecilik belki daha kolay düşünülebilir. En azından mümkün mü sorusunun cevabını mutlak sahteci ararken daha kolay bulabiliriz belki. Ama mutlak sahteci varsa bile bu mutlak sahici olduğu anlamına geliyor mu bilmiyorum. Mutlak sahici tek dinli anlayışta yaradan olur, çok dinlide bilemiyorum. Din dışı anlayışta ise düşünce, eylem ve hatta maddesel olarak kaynaklarımızı daha çözemedik sanırsam. Olayı ‘mutlak’ boyutuna taşıyınca iş çok büyüyor galiba. Konuyu bütünüyle görebilecek kadar mesafe alamıyoruz sanki.

İşin özelinde konuşursam; A4 üzerine yazılmış, bir sahtecinin, yani bir taklitçinin, taklitten mola aldığı bir zamanda (mesaisi bittiğinde) kendini sahici, yani özgün olanla karşılaştırdığı bir metin. Sergide 720 kopya üst üste yerleştirilmiş, bir yılan ya da labirent gibi ilerleyen, sadece en üsttekinin (ve aslında yazıcıdan çıkan ilk kopyanın) bütünüyle okunabildiği bir proje. Metinde Sahteci karakteri kronolojiye takmış durumda; pür dikkat Sahici’yi izleyip, onun hareketlerini anında tekrarlamaya çalışsa da hiç bir zaman onunla eş zamanlı olamayacağının veya onun önüne geçemeyeceğinin farkında. Sahici Sahteci’den bağımsız, alakasız düşüncelerle ilerlerken, Sahteci Sahici’ye mecbur. Sanırım mesai-dışı yazdığı bu metinde bu sebepten dolayı kendi değerini anlama gibi bir çabası var. Sahtecilik de kolay değil, işin başkasını tamamen taklit etmek de kendi içinde bir değer sahibi olabilir mi gibi bir sorusu/iddiası var.

Can an answer be surprising?, 2017-20; video installation. 22 minutes. Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Geç Kalan Yankı eseriniz hakkında konuşulacak çok fazla ayrıntı olduğuna inanıyorum. Hazar Prensesi’nin ve Narcissus’un hikâyeleriyle kendi hikâyenizi harmanlıyorsunuz. Bu iki hikâyeyi anlattığınız sırada herhangi bir yankı duymuyoruz oysa ki size ait hikâyede bu çalışmaya da ismini veren, sesinizin geç gelen yankısı var. Bu özbenlikle ilgili oyunu nasıl kurdunuz?

Geç Kalan Yankı serginin en uzun soluklu projesi aslında. 2016’da bir ses işi olarak başlamıştı, arada bayağı uzayıp sonra tekrar küçülerek en son 14 dakikalık bir video oldu.

Proje, anlatıcının kendini tanıyamadığı bir andan başlıyor. Yüz agnozisi olarak terimlendirilen bu fenomende/hastalıkta karşıdaki yüzü tanıma yetisinin kaybı yaşanıyor. Videoda bahsedildiği halinde sadece birkaç saniye süren bu yeti kaybı, anlatıcının yüzünü tanımlamasına, kişisel tarihini oluşturmasına ve benlik oluşturma süreçlerimizdeki mekanizmalar hakkındaki düşüncelerini paylaşmasına sebep oluyor.

Aslında birinci tekil şahısta ilerleyen, ama sesin farklı kaynaklardan yankılar ile kurgulandığı bu videoya Narcissus ve Prenses Ateh eşlik ediyor. Bu iki karakterin varlığı aslında biliş (kognitif)/algı sürecindeki zaman olgusuyla alakalı. Bu projenin en temelinde eylemi yapan bir “ben”, onu izleyen bir “benlik” olduğu anlayışı yatıyor. İzleyen tabii ki geriden geliyor ve spekülatif bir biçimde “ben”in yaptıklarına anlam yüklüyor. Video, bu aradaki sürenin çok özel bir dengede kurulu olduğuna, çok kolay bozulup kırılabileceğine dair bir argümanda bulunuyor.

Narcissus ve Ateh de bu noktada eylem ile algı arasındaki -veya bu iş özelinde konuşursak- reel ile imge arasındaki zamansal farkın aşırılaşmasıyla olabileceklerin birer örneği olarak yer alıyor. Narcissus çok işlenmiş bir karakter, ama ben bu hikâyeyi ele alırken söz konusu gölün büyülü olduğu fikriyle yaklaştım. Bu büyüye göre Narcissus’un imgesi reel ile eş zamanlı olarak varoluyor ve bu sebepten Narcissus kendi bakışı ile imajın bakışı arasında zamandışı (atemporal) bir parantezde hapsoluyor. Bakışını çekemiyor, tam bir “ben” haline geliyor, iradesiz, pasif bir karaktere dönüşüyor. İmgesinin karşısında eriyip bitiyor.

Ateh ise diğer uçta yer alıyor (“Dictionary of the Khazars”, Milorad Pavić). Ateh’e iki ayna hediye ediliyor ve bu iki aynadan birinde imge reelden bir süre sonra, diğerinde ise imge reelden bir süre önce geliyor. Uyurken onu düşmanlarından koruması için göz kapaklarına yazılmış, okuyanı öldüren büyü ise bu iki ayna yüzünden prensese görünür kılınıyor ve prensesin sonu böyle geliyor. Çünkü; aynalardan biri bir önceki göz kırpmasını gösterirken, diğeri bir sonraki göz kırpmasını gösteriyor. İki göz kırpış arasında Ateh büyüyü okuyup ölüyor.

Bahsettiğin gibi videoda Narcissus ve Ateh hikâyeleri tek ses ve merkezden gelirken, anlatıcının kendini kurguladığı ve anlattığı zamanlar yankılı, yansımalı ve parallelli. Soyut bir alternatifi ya da dış olarak kabul ettiğimiz bir olguyu değerlendirirken aslında daha kesin ve keskin olabildiğimizi düşündüğüm için böyle bir seçim yaptım. Ama aslında iç-dış, ben-öteki gibi indirgeyici ve zararlı ikilikleri aşıp, daha ötesinde evrensel bir noktaya ulaşmaya çalıştığım bir proje.

Sergi künyesi: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021. Fotoğraf künyesi: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

Benim bu sergiden etkilenmemin önemli bir sebebi; serginin herhangi bir sosyo-politik, güncel dünya sorunları hakkında doğrudan bir görüş bildirme kaygısı taşımamasıydı. Günümüzde sanatsal çalışmaların sosyal ve politik olaylarla alakalı olması dayatmasının rahatsız edici bir ısrarcılığa dönüştüğünü düşünüyorum. Kafakurcalayan sergisinin olağanca bireyselliğinin içinde hepimizin aklından geçen birçok varoluşsal konuyu ortaya koymasının vurucu olduğu kanısındayım.

Güncel/çağdaş diye isimlendirilen günümüz sanatına adını bile vermiş olan, en önemli özelliği bugünün mevcut dertleri ile uğraşmak diye düşünüyorum ben. Ama bazen bugünü oluşturan şeyleri çok kısıtlı alıyoruz gibi. Bugün dediğimiz, yani ele aldığımız zaman daraldıkça şimdide kısıtlı kaldığımız bir duruma giriyoruz. Neredeyse Narcissus’un bakışı gibi. Kendi parantezinde kapanan, sıkışan, ileri geri gidip gelen bir ışın gibi. Benim niyetim aslında hem biraz bu parantezi genişletmek, hem de bu bakışı kırmak, başka perspektiflere olanak sağlamaktı.

Bu noktada sosyo-politik alan ile ilişkili olmak için bugünün acil sorunlarını illa ki konu olarak ele almamız gerektiğini düşünmüyorum. Sanat işi bir bilinmezi açığa çıkarma, ütopya sunma, kitlelere ulaşmanın yanı sıra bir konuya olan yaklaşımı, ele alış biçimi, yani estetiği ile de politik olabilir diye düşünüyorum.

Kafakurcalayan, teknoloji ile birlikte sürekli değişim içinde zaten bulunan -ve belki daha çok değişim geçirecek olan- birey, beden, iyelik (ownership) ve faillik (agency) anlayışlarımız üzerine çalıştığım bir sergi oldu. Bu tarz varoluşsal konuları çözümlemeye çalışırken kullandığım, bana yardımcı olan araçları bu sergi aracılığıyla izleyiciye açmış bulundum. Bu benimsediğim yöntemin de karşılaşmalara, empatiye alan açtığı için ve genel olarak yavaşlatma çabasında bulunduğu için sosyo-politik alan ile münasebeti olduğunu düşünüyorum.

Merve Ertufan

Merve Ertufan - Kafakurcalayan - Depo İstanbul (depoistanbul.net)

Teşekkür listesi: Merve Ertufan, Tomris Melis Golar, Gülşah Mursaloğlu, Mochu & Depo İstanbul